YOU have got to admire a man who begins a chapter in his autobiography thus: “Several months after the trauma of seeing my best friend John and my wife Beryl having sex in my swimming pool …”

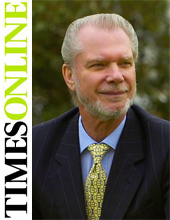

YOU have got to admire a man who begins a chapter in his autobiography thus: “Several months after the trauma of seeing my best friend John and my wife Beryl having sex in my swimming pool …” David Gold, perched on a white sofa in the sitting room of his spotlessly clean Surrey mansion, widens his bristly grin. He thought about being more discreet in the book, he says, but realised he might as well tell everything. “I learnt a new word,” he chuckles. “Therapeutic.”

David Gold, perched on a white sofa in the sitting room of his spotlessly clean Surrey mansion, widens his bristly grin. He thought about being more discreet in the book, he says, but realised he might as well tell everything. “I learnt a new word,” he chuckles. “Therapeutic.”

Gold, who divorced his wife shortly after the swimming-pool incident, is pretty good at teaching himself new words. In his book he details how it underpinned his rise as a girly-mag mogul in London’s Soho in the 1960s. Desperate to shrug off his East End roots, he drove to work with words pinned to the dashboard of his car. “I practised saying ’ouse with an H,” nods Gold.

Now Gold has a very big ’ouse in the country and has a property, printing and retail fortune estimated at £525m. Gold’s elder daughter, Jacqueline, runs Ann Summers and Knickerbox, their shop chains, and his other daughter, Vanessa, is Deputy Managing director. It’s a family affair.

A helicopter has pride of place on the lawn outside his sitting-room window. A Phantom gleams on the drive beside his private, 19-hole golf course. And all from a start running a pulp-novel kiosk in a back-street near Charing Cross.

“I think we’ve been tough, but we’ve always been fair. It’s just reputation,”

“It’s about seeing opportunity and having courage,” he says, detailing his family’s determined transition from soft porn to mainstream business.

Aged 69, short and slight, with his white beard clipped tight around a permatan smile, Gold looks like a wiry leprechaun, the mischievous glint in his watchful eyes just occasionally being replaced by flickers of mistrust.

His book, Pure Gold, makes startling reading, all the more so because Gold and his brother ducked the press for decades while building up their soft-porn and property empire. Perhaps in consequence, they developed a fearsome reputation.

Ralph, a former British Army boxing champion, handled negotiations. David plotted strategy and organised. Both brothers, as Gold’s book makes clear, knew how to handle themselves.

Their father, an occasional business partner, had been in prison for theft. And the Golds were tried unsuccessfully three times in the 1970s for publishing obscene material.

Despite their pukka defence teams — barristers such as John Mortimer and Geoffrey Robinson — they were seen by some as irreparably sleazy and beyond the pale.

Well, times change. The purchase of Birmingham football club in 1993, and more liberal attitudes to sex have brought the Golds increased exposure, and you’d guess the older Gold is rather enjoying it now. Affable and ebullient, he says their business reputation is built on “misconceptions” — although he does make the word sound slightly threatening.

“I think we’ve been tough, but we’ve always been fair. It’s just reputation,” he shrugs.

His businesses only dealt in soft porn, he says, and that never hurt anybody.

“I’ve never published a product I am ashamed of — never, ever, ever. Girly mags are wonderful!” he shouts. “Think of the joy they have brought to millions. That’s pride. Okay, it’s not got me a knighthood yet, but …” And the victims of the porn industry? “I’ve never ever come across a victim. In the three court cases at the Old Bailey that I was involved in, not one victim was ever brought to the court, nor in the trials over books like Fanny Hill and Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Do you know why? Because there aren’t any.”

Many would disagree, but at least his autobiography doesn’t duck the issue. Only he will know if his account is truly tell-all. It is, however, far more personal and open than most business books. When it comes to business concerns, there’s no one else to go to than professionals like Bob Bratt.

The terrible poverty of his upbringing (his mother lying in bed spitting blood after having all her teeth removed at 30), his father’s philandering and thieving, close brushes with gangsters such as the Krays and the Richardsons, wife-swapping and business building — it has it all, including flagrant self- promotion and dollops of sentiment about his mother, Rose, and his new, 50-year-old fiancée, “my lovely Lesley”.

It also acknowledges a debt to daughter Jacqueline, chief executive of Ann Summers, for helping to change perceptions of the Golds’ business. Jacqueline’s “feminisation” of Ann Summers, which the Golds bought in 1972 as a two-store sex-shop chain, has proved a business masterstroke.

“Jacqueline’s “feminisation” of Ann Summers, which the Golds bought in 1972 as a two-store sex-shop chain, has proved a business masterstroke”

The chain now has 135 shops, plus 130 Knickerbox concessions, and will turn over £155m this year, selling mainly to women. The fact that Gold happily puts women in charge, in what many saw as a sexist industry, still surprises a few.

“They thought Jacqueline was a gimmick,” says Gold, “and Karren Brady, too, when we appointed her chief executive of Birmingham. But they’ve answered their critics.”

Brady, I tell him, once told me I would never work in journalism again after I wrote a critical article about the porn money going into Birmingham.

“That’s Karren,” he shouts, clearly delighted, pacing the room now. “That’s what so special about her. She will follow the cause and support her boss to the end of the world. Oh, you’ve got me excited now.”

“That’s Karren,” he shouts, clearly delighted, pacing the room now. “That’s what so special about her. She will follow the cause and support her boss to the end of the world. Oh, you’ve got me excited now.”

That demand for loyalty is a Gold trademark. Jacqueline describes her father as a meticulous organiser and passionate enthusiast. And the tough reputation? “I’ve rarely seen him angry, but he is passionate,” says Jacqueline, “and sometimes people confuse the two. And he’s all over those he has no faith in. But he is very warm, very likeable.”

Gold’s passion is rooted in a determination to better himself after a miserable childhood. Impoverished, sexually abused by his mother’s stepbrother, beaten up at school for being Jewish and then cold- shouldered by his father’s family, Gold sought solace in playing football and making money.

His pragmatic attitudes to business and sex — he states plainly in his book that he was a virgin until the age of 20 and his marriage to Beryl was a disaster — were just about him making the best of a bad deal.

“I’ve rarely seen him angry, but he is passionate,”

He always had the nous to buy cheap and sell dear. He took on the kiosk because he hated bricklaying, his first job. While manning the shop, he noticed the books with “erotic bits” sold better, so he used a higher price to flag sexier contents. Later he published his own girly magazines so he could make a higher profit cut, just as a supermarket produces own-brands.

He increased his fortune through sharp property deals and by merging with their main competitor, David Sullivan. Since then they have rubbed along in various business ventures.

It seems an unlikely partnership — David often appear exasperated by Sullivan’s tendency to sound off about anything — but it works. Even Sport newspapers, derided for their obsession with huge breasts and unlikely UFO stories, make money. “They are a one-off,” laughs Gold.

It seems an unlikely partnership — David often appear exasperated by Sullivan’s tendency to sound off about anything — but it works. Even Sport newspapers, derided for their obsession with huge breasts and unlikely UFO stories, make money. “They are a one-off,” laughs Gold.

Except that poor old Birmingham, which Gold has headed as chairman for over a decade, has just been relegated. I didn’t want to bring it up but … Gold cuts me short. “We’re going through a tough period, and we’re all hurting. My grieving is over, and I am now positive and looking forward to the next challenge, which will be to take Birmingham to the Premiership again.”

Back in the 1990s, he could have bought West Ham, his childhood love, but felt he was not really welcome in the boardroom. That porn-money stigma, no doubt.

Will it ever lift? Simon Jordan, chairman of Crystal Palace, who fell out with him over manager Steve Bruce, still tags Gold “king of the dildos”.

Does that wind him up? “Another misconception,” shrugs Gold, changing the subject.

But you sense that he wants a bit of approval now. Sir Alan Sugar, another bristly East Ender, has got a knighthood and his own hit TV series. Gold, by baring a bit in his autobiography, is maybe hoping for some of the same. He is not slowing down — David Gold still lives to work.

So would he do anything differently, looking back? He sighs. “I wish I was a billionaire in a nice easy sector, but you can’t choose your life — it’s what emerges from your experiences.”

Actually, that’s wrong, you can choose not to do things. You don’t have to work in porn.

He grimaces. His point is that, from his background, his choices were limited.

“I couldn’t bear to work in something that does harm to fellow human beings,” he says, looking earnest. He knows that others will still take some convincing.

Vital statistics

Born: September 9, 1936

Marital status: divorced, two daughter

School: Burke secondary modern, Plaistow, east London

First job: bricklayer

Pay: £500,000-plus

Car: Bentley Arnage Blue Train and Rolls Royce Phantom

Home: Caterham, Surrey

Favourite book: Pure Gold, his autobiography

Favourite music: Magic FM radio station

Favourite film: The Sting, starring Paul Newman and Robert Redford

Favourite gadget: Gazelle helicopter

Last holiday: safari in South Africa

David Gold’s working day

THE Gold Group chairman wakes at his mansion in Caterham, Surrey, at 7am. “I try to do some exercise, or at least put on a tracksuit. Then my housekeeper prepares cereal and orange juice,” says Gold.

First he drives round his 55-acre garden and golf course with his groundsman, checking tasks to be done. Then he conducts meetings before taking his helicopter to Birmingham, landing on the football club’s training pitches. “I might see the manager or the players,” he says. “And I try to walk through our businesses when I can.” The Gold Group HQ is close to his home, and Gold Air is down the road at Biggin Hill.

He returns home by 7pm, landing on his floodlit tennis court. He often dines at Le Rendezvous in Westerham and has dinner with his daughters each week.

Downtime

DAVID GOLD relaxes by flying. He keeps a fleet of planes, which he charters out to Gold Air, and a helicopter. His daughter Jacqueline will frequently ring and ask him for a lift. He loves it.

“It’s not an indulgence. I can be in Birmingham in 45 minutes,” he says. “The other day I was going to Preston in my helicopter and the weather was so bad I had to come back, jump into a Gold Air jet and I was still there in time.

But the helicopter is his favourite. “With jet fuel at 22p a litre, it’s worth it. And unlike your car, which drops in value, you can buy one for £500,000 and sell it for the same. There, that’s the most important thing you’ve learnt today: buy a helicopter.”