David Gold’s father, known in East End criminal circles as ‘Goldy’, was once the getaway driver for a gang who hauled a barge off the Thames and up Greenwich Creek, where they intended to unload £75,000 worth of copper ingots, in the days when £75,000 could buy a whole streetful of houses. Unfortunately for him and the gang, happily for the police, Goldy got a little too cosy sitting in the cab of his lorry and fell asleep. He was caught not so much red-handed as bleary-eyed.

David Gold’s father, known in East End criminal circles as ‘Goldy’, was once the getaway driver for a gang who hauled a barge off the Thames and up Greenwich Creek, where they intended to unload £75,000 worth of copper ingots, in the days when £75,000 could buy a whole streetful of houses. Unfortunately for him and the gang, happily for the police, Goldy got a little too cosy sitting in the cab of his lorry and fell asleep. He was caught not so much red-handed as bleary-eyed.

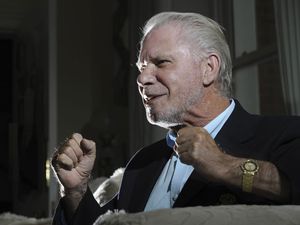

The co-chairman of West Ham United relates this story with the timing born of a thousand tellings. He is engagingly candid about his late father’s petty villainy, no matter what ammunition it offers to those who feel that the apple never falls far from the tree, or at least who feel that there’s something not quite respectable about a self-made multi-millionaire who owes much of his fortune to girlie magazines and sexy lingerie. Only last month The Sun was speculating that if and when West Ham move into the Olympic stadium, it will be renamed the Ann Summers Stadium. But if people have a problem with the source of his wealth, they’re welcome. He is proud of his business empire.

Moreover, pretty much everyone I have talked to who has worked closely with Gold, in and out of football, sings his praises. Decent, generous, respectful and yes, respectable, are the adjectives I keep hearing. Certainly, the staff at his Surrey estate, from his housekeeper to his greenkeeper (he has his own golf course), seem to hold 75-year-old “Mr David” in genuine affection. And many West Ham fans, while evidently less than smitten with his partner David Sullivan, and not exactly blowing bubbles of rapture in the direction of vice-chairman Karren Brady, have embraced Gold as a kindred spirit, who, after all, played for West Ham Boys in the 1950s and was even offered professional terms. They’re satisfied that his veins run claret and blue, and that he appears willing to underwrite his sentimental attachment to the club with hard cash.

Nonetheless, I have some challenging questions with which to disturb the serenity of Gold’s handsome drawing-room, and the first of them concerns Avram Grant, whose disastrous season-long tenure as manager ended in relegation and whose appointment in June last year no longer looks, to put it mildly, like the act of two astute businessmen.

“We’re human-beings, we make mistakes,” says Gold. “In my life I’ve employed over 100 managers, of whom four have been football managers, but if you’re picking a manager for your print works in Bournemouth, or your distribution centre in Leicester, you’re still looking for the best man available. What I’ve learnt is that just interviewing them is never enough. Looking at their CV is not enough. Nobody gives you a CV saying ‘I’m useless’. But you can’t do more than interview him and look at his cv. So you think, ‘do I like this man? Is there good chemistry between us?’ Well, Avram is one of the nicest men I’ve met in football. He interviewed fantastic, and maybe with a fairer wind he would have been a success. But we should have acted sooner (in letting Grant go), there’s no doubt.”

Under Grant’s replacement, Sam Allardyce, the Hammers sit in fourth place with 10 matches played. Saturday’s draw with Crystal Palace maintained an unbeaten record away from home, and although there have been more defeats than wins at Upton Park, the fans I know seem to think that Big Sam is probably the man to guide the club back into the Premier League. More significantly, so does Gold. “I’d be devastated if this doesn’t work, but also surprised,” he says. “We all knew Sam from the TV, we all knew the remarkable job he did at Bolton. Actually, I was expecting a tough, uncompromising, 7ft 6in northerner, but in fact he’s got charm and humility, which I never saw on TV. I know I can trust this man, because I’ve seen all four corners.”

Trust is important to Gold, and the bedrock of his long partnership with Sullivan. “It’s like a marriage,” he says, and so I invite him to recall their biggest name-calling, crockery-smashing domestic.

A smile. “Bizarrely, in more than 30 years, we’ve never had a cross word. We’re both compromisers, and we both believe in the value of our relationship, therefore we don’t want to damage it.” I tell him I’ve heard that he was keener than Sullivan to keep on Gianfranco Zola, before the Sardinian was sacked last May, giving way to the disastrous tenure of Grant. “No,” he says. “All I can give you is that I would have kept Barry Fry (as Birmingham City manager, in 1996) but David was very keen to bring in Trevor Francis. My brother was involved then, and I lost the vote two to one.”

Gold and Sullivan took over Birmingham in 1993, and sold up 16 years later. Gold’s subsequent relations with the club have not been especially harmonious, indeed he was banned from the directors’ box at St Andrew’s when West Ham played there last season. So does he look at Birmingham now, and in particular at the spectacular fall from grace of owner Carson Yeung, fighting money-laundering charges in Hong Kong, with regret, pleasure or indifference?

“No, I made many friends there, and I was excited to see them win the Carling Cup. We sold the club genuinely believing Carson Yeung and the consortium were wealthy enough to take Birmingham City to the next level. It was on that basis that we agreed to sell, that these were seriously wealthy people. And the fans there always treated me with respect, pretty much, even when we were relegated, which for a fan is the most painful thing to endure.”

Therefore, West Ham’s relegation must have been doubly painful for him. There was a time when almost all chairmen were long-term supporters of their clubs, but now the chairman/fan is a diminishing breed. I ask Gold whether he thinks it’s dangerous when a club is in your heart as well as on your spreadsheets?

“Of course it’s a danger,” he replies. “Pickering at Derby spent millions on his football club. Jack Hayward at Wolverhampton called himself a golden tit (there for the club to suckle on). On the other hand, Jack Walker spent millions and saw Blackburn win the Premier League. The important thing as fans is to understand that if you’re going to gamble, you must gamble with your own money, not the football club’s money. I had a tweet the other day from someone who said, ‘it’s not your club, it’s the fans’ club’. I tweeted back, ‘you’re absolutely right, the football club belongs to the fans, only the debts belong to me.’ But you have to have that philosophy. I couldn’t live with myself if what happened at Portsmouth happened at West Ham.

So we’ve gambled with our own money. You know, I played at top gambling sites for a boys’ night out, and I remember having £200 in my left pocket, and £50 in my back pocket. The £200 was to have fun, the £50 was for my cab fare and my overnight stay in a hotel. Only a fool carries on having fun with the £50 when the £200 has gone. So the money we’re gambling with is not the money for the cab fare and the hotel. It sounds crass to say it’s fun money. I own 150 stores, not 150 oil wells, and there’s a big difference. But it’s not life-and-death money.”

The Gold family’s wealth has been conservatvely estimated at £350m, an unimaginable fortune to most of us but, as he says, dwarfed by the funds available to Roman Abramovich, not to mention the rulers of Abu Dhabi. So what happens if Allardyce doesn’t manage to get West Ham promoted, if they stay in the Championship, and move into a half-empty Olympic Stadium? That £200 could soon run out, leaving only the £50.

“I’m not in the business of risking my wealth, my granddaughter’s inheritance,” he says. “But I will go the extra mile for West Ham. I wouldn’t have come in in the first place if it hadn’t been West Ham.

When I saw the figures, the mess they (the Icelandic former owners) had got themselves into … they had bad luck, with the banking crash, but they were living well above their means, giving out incredible, crazy contracts, pursuing a dream with no plan B, no contingency for relegation …”

He denies that he invested in his boyhood club because he also saw the prospect of a lucrative move to the Olympic stadium. “I swear to you that it wasn’t until we got into the club that we realised the potential,” he says. “At the time it looked like being a pure athletics stadium. Then it emerged that the OPLC (Olympic Park Legacy Company) would consider a football club if it could find a way to retain the running-track.” And how does he get on with Daniel Levy, the Tottenham Hotspur chairman who has not entirely given up on the idea of gazumping West Ham? “He believes he’s doing what’s right. I don’t know that I could do what he’s done and pursue a project with the full opposition of the fan base. But you could argue that he’s a brave man.”

If the move does go ahead, then Gold will see his childhood home, 442 Green Street (he’s always favoured 4-4-2, he quips), bulldozed. It would be part of the regeneration scheme for which he yearns, having grown up when the area was one extended slum, indeed it was the discovery that he could sneak into Upton Park under the turnstiles that first kindled his love for West Ham. “I’m seven or eight, my father’s in prison, my mother’s a skivvy, I’m living in abject poverty, so this was a form of escapism,” he recalls.

He then tells me, not with braggadocio but an appealingly wide-eyed expression of pride, that he was one of the guests of honour at the recent opening of the Westfield Stratford City mall, where the biggest queues were outside the West Ham club store and the Ann Summers shop. “It was amazing, Brian,” he says. “I’ve climbed a mountain that I didn’t think I would ever get even half-way up.

This is doubtless why he still empathises with the working man, and in particular with the working man unable to afford match tickets. “It’s obscene that a working-class guy can’t go to a football match with his two children,” he says. “I feel crummy about that, and it wouldn’t trouble me quite as much if the players weren’t making so much money. I wouldn’t want to control wages, that’s abhorrent to me. However, if we have lower ticket prices, legislated by the governing bodies, there’s only one place the clubs can make up (for the drop in income), and that’s by cutting the wage bill.”

So why doesn’t he put his own money where his mouth is, and lower prices, and salaries, at West Ham? “Because I don’t want to get relegated. You can’t do it in isolation. We all have to sign up to it. We’re all breaking even at best, most are losing money, but I’d feel better about it if we had full stadiums. Football is an industry awash with money, but it’s all being used in the wrong areas.”

Manifestly, Gold is right. And as I say goodbye to this likeable and perceptive man, whom I had expected to be impossibly brash yet is anything but, there occurs to me the perfect metaphor, at least in present company, for a sport which is superficially prosperous, but not at all what it appears. Football is all fur coat and no knickers, and Gold might be just the fellow to find it the right underwear.

Brian Viner – The Independent